A Moment of Your Time, Please...

Once upon a time there was a magazine called Cult Movies. Everybody loved it. It had terrific pictures and cool interviews and wonderful articles and we all bought every issue as soon as it came out. And then, it stopped. Time marches on but we all get older and trends change. Print is fast being replaced by the internet (Hey! You're reading this online, aren't you?!) and in small press, one must eventually pull the plug.

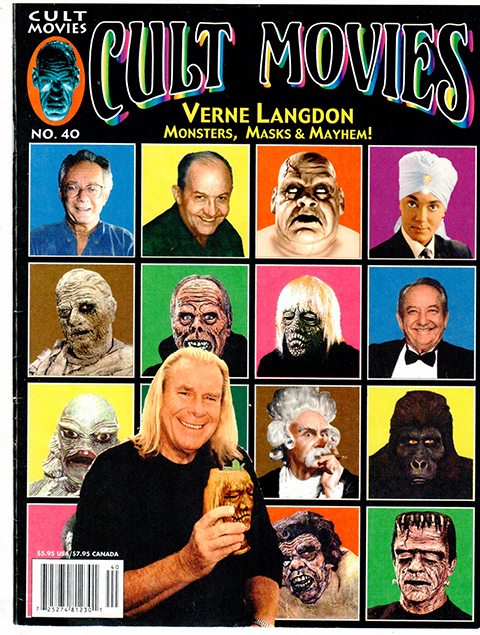

By the time issue 40 came around, distribution was WAY down and there weren't that many copies to be grabbed up at newsstands. Not like the good old days of the latter half of the 20th century. And so the articles and interviews in issue 40 are only famous now in legend and song.

Naturally, we wanted to do something about that. And so, in honor of Forrest J Ackerman's 102nd birthday (in this year of grace two-thousand and eighteen), Buddy Barnett and Michael Copner agreed to let us reprint this wonderful interview with Mike and legendary monster publisher James Warren.

We've added a few more pictures... Enjoy!

James Warren Live!

Reprinted with Permission

From Cult Movies #40

interviewed by Michael Copner

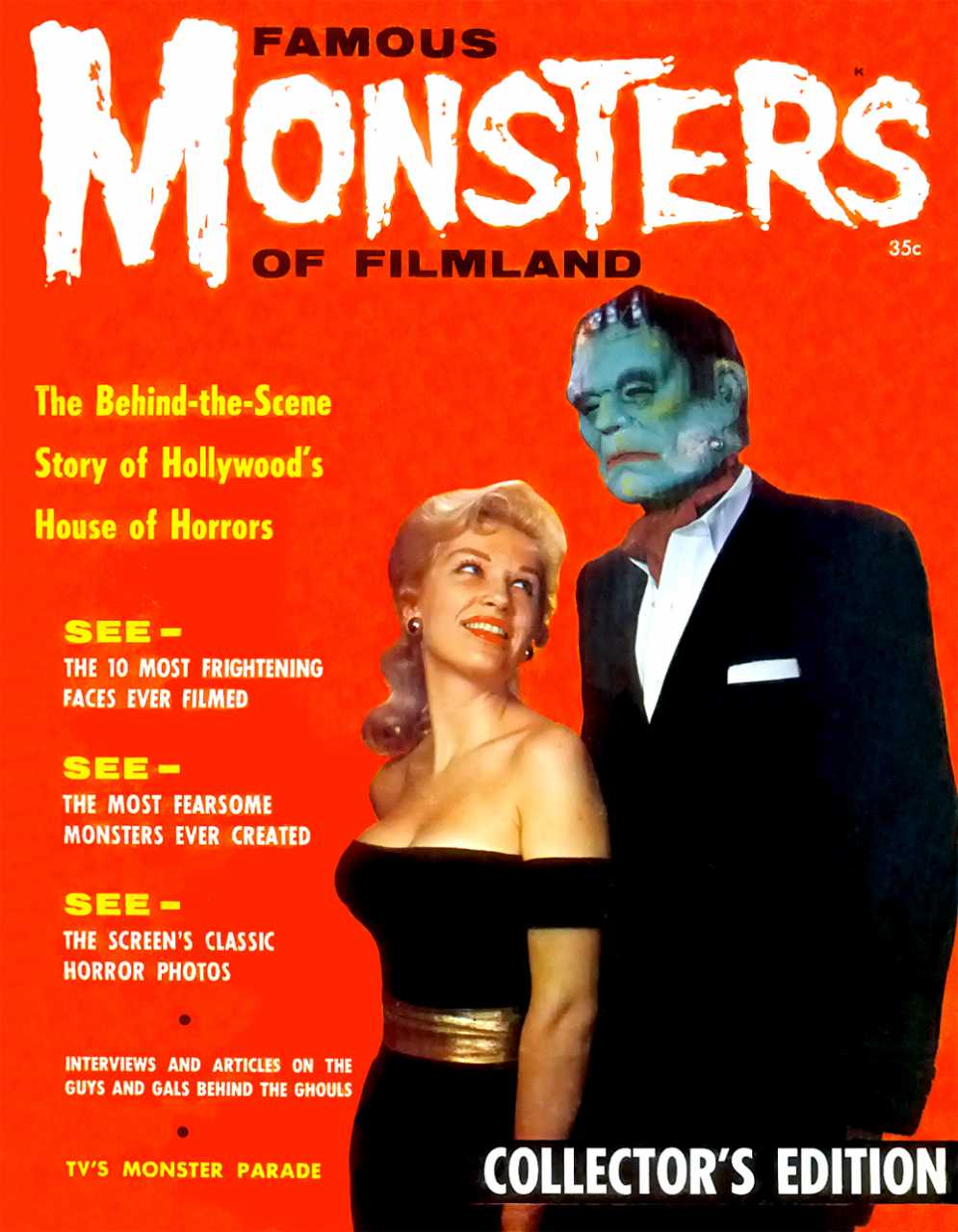

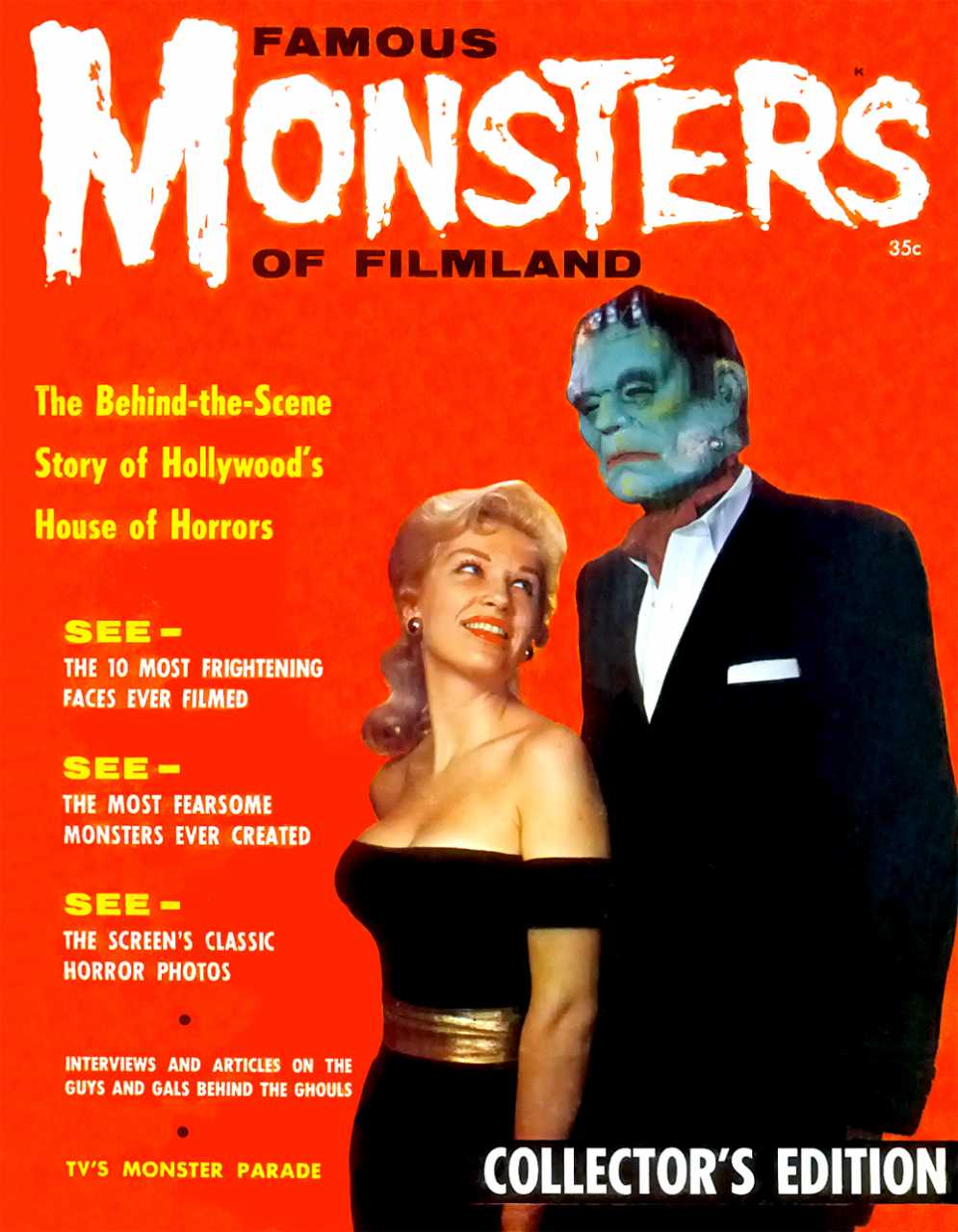

On November 22, 2003, Verne Langdon provided the most surprising birthday surprise anyone could have given to Forrest J Ackerman on the occasion of FJA's 87th birthday, by producing none other than James Warren, the originator and 1958-1984 publisher of Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine.

In addition to FM,the team of Warren & Ackerman created many other magazines which inspired the phenomenal American monster craze of our young generation, including Vampirella and Monster World.

James Warren and Forry Ackerman had not seen each other in several decades, and the birthday time reunion was an emotion filled event, a historical moment which still reverberates with potential. During his extended stay in Southern California, Mr. Warren was involved in numerous ongoing monster-related business meetings.

After Forry's birthday party, Mr. Warren granted us an exclusive interview regarding the birth of FamousMonsters, how the Warren publishing empire helped shape our American popular culture, and a look to the future.

Cult Movies: We want to talk to you about the distribution of your magazines, which was a very important factor to us in the 1960s. Famous Monsters was hard to find on the newsstand, which made it all that much more valuable when we did find it.

James Warren: The major reason behind that was that we'd started a new genre, and newsstand managers didn't know what to do with us or where to place us on the news racks. Some put us with movie magazines, while some put us with Mad Magazine. There was no consistency.

CM: Where would you prefer to have been placed?

JW: I would have preferred to own all my own newsstands, in order to get the job done right. But barring that, I told news dealers to place FM somewhere between the comic books and Mad Magazine. I said, “that doesn't mean our customers, are exactly the same kind of customers when you place us in the drugstores or on the newsstands." I just felt that if we were in that general area of interest, then our covers should be of sufficient interest to take over and create the sales. But not if we got lost with the movie magazines. Or even worse, with the photography magazines. Some dealers thought of us as a photography journal with the black & white photos, so they'd place us in that section, where we'd also lose sales.

They had to be told. They didn’t have the knowledge, the understanding or inclination to consider that this was something special, just as Mad and Playboy had been when they first premiered. So we were breaking new ground, and I was still an outsider looking in. I learned that in each city and territory, magazine distribution is a monopoly. Many of the people, in this business came from the seamier side of society. They weren't exactly the underworld but they were close.

CM: I recall reading that you'd done some advance publicity before Issue #l was printed, and then there was some delay. But I can't remember what the delay was.

JW: There was no delay on my part. Every magazine has an on-sale date, though few publishers meet that date 100% of the time. FM was printed on time, and then the Northeast section of the U.S. experienced the worst storm in 50 years. The trucks were snowed in and couldn’t take the magazines from the printers by road or to the trains for national distribution. It took three weeks afterwards before the roads were sufficiently cleared.

CM: And in that three weeks the distributors had a chance to forget your advance promotion,

JW: "Forget" is not the word. I was a small independent. FM was my only magazine and my promotion was forgotten the minute I spoke it. Three weeks after that storm, a lot of the distributors had completely forgotten me. I had to get back on' the phone with many of them, and they’d say, "Kid, don't bother me! I've got important things to do!" I was 28 years old and got called "kid" a lot. I had to grin and bear it and work it out. They didn't understand what our magazine was about and they really didn't care.

CM: Were you providing any point-of-purchase extras like posters or cardboard display boxes to place them in?

JW: No. My net worth at the time consisted of 12 pizza discount coupons, three of which bad already expired. There was no money for extras beyond printing.

CM: Do you recall the print run of that first issue?

CM: Do you recall the print run of that first issue?

JW: Sure. Don't you recall your birthday? The first print run was 200,000. And once it got to the public, there were many areas where it sold out within five days.

CM: And that's when history was made.

JW: That's when the' wholesalers weren't calling me "kid" anymore. Some of them still didn't understand the concept, or what had happened in five days, but we knew we had a hit on our hands. Reports were flying from all over the country that, "We've got this dumb thing with a kind of Frankenstein whatsit on the cover. I don't know what it is, but it's all sold out! We want a re-order!" Some of them wanted to double the previous order. When you're getting that kind of response from Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and five or six other key areas you know it's a hit. So we went back to press and printed another 200,000. And with the exception of perhaps 10,000 copies we sold out the entire print run on those books.

CM: In those days were you having to take the distributors’ word for how many copies were sold?

JW: We had to take their word, and their word was absurd because they lie, cheat, and steal. In major cities the distributors had the right to give you an affidavit, signed in front of a notary public, stating that unsold copies were destroyed. But they never destroyed them. First of all. if they sold 70% of what you shipped them, they represented that they only sold 50%. And then they took the rest and sold them illegally. There was a time when I was considering a federal lawsuit against all the distributors for fraud, and my attorneys advised that I could possibly win millions in damages, but I'd be out of business because no American distributor would touch my products again. On the other hand if a court decided against me, I'd lose the case and still no distributors would ever handle my magazines again. My attorneys felt a few dealers might even put out a hit on me. So it was a very tough time in the late 1950s. But we did succeed by showing them that "the kid" had something. Even if the more experienced pros didn't know why our magazines were popular, the young generation knew exactly what we were all about. The second battle I had to fight in addition to distribution, came as a surprise because none of us saw it coming. And that was the religious battle. The Catholic schools came down on me; the diocese of Philadelphia and Boston, who accused me of blasphemy for having a magazine about movies like Frankenstein, showing life created by science rather than by deity. Of course, now with cloning and organ banks, we know this is at least possible and can serve as a force of good for mankind. But then it was pure speculation and science-fiction, and it was construed as a gift from the devil. At first I thought it was a real reach and nothing to be concerned with. But then I saw they were serious, especially when they started picketing our wholesalers and retailers: Particularly if our dealer was Catholic; he'd cease selling us right away.

CM: And the fact that these movies were based on folklore or classics of literature meant nothing?

JW: You'd think it should have meant something to school teachers, who should have known better. But our magazines were confiscated in schools. I went to PTA meetings to discuss the subject, and when I referred to these classic films as an art form, I was laughed out of the room. The adults had no appreciation of the genius that went into the music, lighting, make-up, and the talent of actors like Karloff and Lugosi which all made these films a valuable art. History has shown me to have been 50 years ahead of the times, since the Federal Government put the movie monsters on a postage stamp series a few years ago. Ten-year olds take these films for granted now. But when we started FM we were an enigma, greatly misunderstood just like the monsters themselves! When I first met Verne Langdon he was being persecuted for creating the Universal monster masks at Don Post Studios. Complaints arose that our young readers were wearing them at Halloween.

CM: Who was persecuting?

JW: The Philadelphia school system held a PTA meeting to address the problem, just to give one example. That's the city where our offices were, and I attended the meeting. They said, "Better our children should be wearing Donald Duck or something from The Wizard of Oz than these awful Frankenstein faces." Again, they thought this was of the devil. How are you going to respond to a thing like that? Verne Langdon was a member of Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Clown College Faculty. He knows make-up, entertainment, as well as kids and how their minds work. As we all know now, the kids identified with the monsters. The writers shifted our sympathies by making the torch-bearing villagers the wrongdoers and violators. The Frankenstein monster became a rebel, loveless yet loveable at the same time, because he never harmed anyone until he himself was harmed. The same went for the Creature, the Wolf Man, and most of the monsters. This promoted acceptance in the mind of the viewers, and food for thought, along with the chills and thrills. It's a main reason why these films are revived today, still considered contemporary in fact, while many films of the 1930s are forgotten. But critics have always said, "No, don't tamper with the formula and humanize the rebel or the monster. There's the white hats and the black hats and bad guys belong behind bars." But since the authority figures couldn't display that outlook personally to Boris Karloff, they took it out on me. I was the one producing this magazine and kind of a focus of their anger.

CM: My teachers in the third grade told my parents to burn my copies of FM.

JW: That was going on all over the country. Students would call me or write me locally in Philadelphia and tell me these stories, and I'd send them another copy. But I'd tell them, "Don't take it to school." And I'd also ask them, "What's the name of your teacher?" And I'd write a personal letter to the teacher explaining my viewpoint as we've been talking about it now.

CM: You got that involved?

JW: I had to. Nobody knows what I did to try and attain acceptance for our publications. Forry Ackerman never knew; he was living on his own planet and doing his own thing. And he was very fortunate, growing up with grandparents who took him to horror films every week back in the silent era, and they all loved them. It was very different for Forry, since he didn't grow up in the world of, "This is bad!" And the magic he worked in the magazine helped create geniuses like Spielberg, who was a young member of our early monster fan club. And I keep thinking back to that amazing turn-around of the movie monster postage stamps. That might not have happened without FM. I wonder if Cult Movies has some readers who think you should be writing more about Gone With the Wind, and less about these horror films. When I was younger, we had cult movies, but we didn't call them that. You want to know who my cult heroes were?

CM: Sure!

JW: The Dead End Kids.

CM: So you got a new cult film every month.

JW: That was later, as the East Side Kids, when they cranked out dozens of films at Monogram. But when I saw Gabe Dell, Leo Gorcey, Huntz Hall, and Bobby Jordan in that 1937 film with Bogart, they became my anti-establishment cult heroes. Any time Dead End would be re-issued at the theaters, I'd go see it.

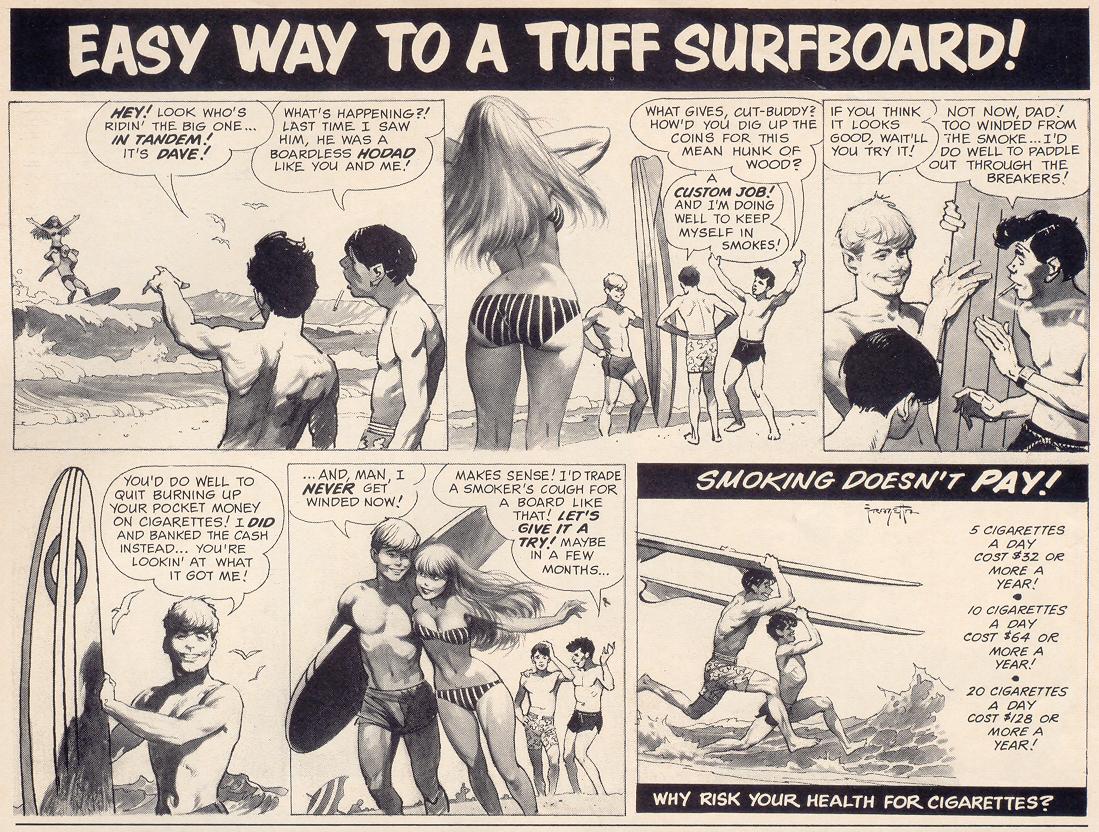

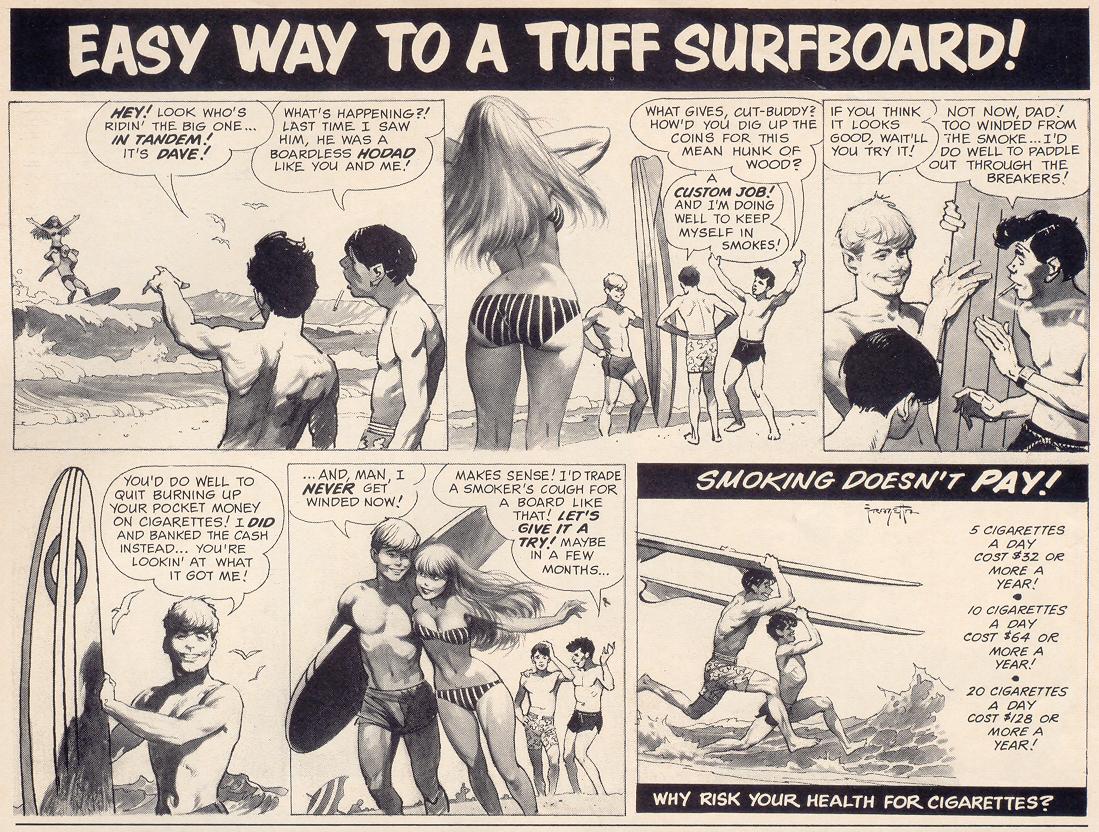

CM: (Verne Langdon interjects): You're a rebel in a variety of ways, like when you ran that anti-smoking public service announcement in all your magazines.

JW: I did that for several runs, not just to be a rebel. An ad agent came to me from one of the big cigarette manufacturers. He knew that we reached a great deal of the youth market, and that to perpetuate cigarette sales on into the next generation and put his own kids through college, he should zero in on our readers. I was taken to lunch on Park Avenue in New York, in the mid-1960s. and I'm talking to this agent He's ready to buy all our back covets in color, and he wants to know our open ad rate. I was going to tell him some absurd low figure like $200 per issue, just to close the deal. But I still didn't know what he would be selling. Now by the mid-60s, everyone knew cigarettes were addictive, even though they still lie and claim they didn't know. And they knew it caused cancer. They'd known since the '40s. At any rate, Warren Publications had a lot of titles going, since we'd introduced Vampirella magazine by then. And this guy said, “Give us all your back covers for all your magazines and we'll give $25,000 for the year." Now can you imagine how much that would have meant to us then? But I said, If I don't care much for smoking, I don't think it's good- for kids or adults." So he said, ''Then we'll make $30,000." Again I declined.

He said, "You're a tough customer, aren't you?" Then in his arrogance, he said, "Okay, name your price." I couldn't believe what I was hearing. So I said, "$100,000 for the year." To which he replied, we'll get back to you." I couldn't believe what was taking place. On the one hand, I didn't want his ads. Yet I would have killed for a $l00,000 guarantee. Strangely enough, he was true to his word. He got back to me that same day. By the time I got back to my office there was a message there to call him, which I did. Suddenly, with this one guy, I was "kid" again. He said, "Kid, a hundred thousand is out of the question. But we'll give you $50,000 for the year." An offer which I declined. That's when I started to think about the arrogance of the individual and the industry, the misuse of power, and decided to have that public service ad made.

CM: That was an effective comic strip. The young guy with his arm around the chick in the bikini, and his line about, "I NEVER get winded now!" Because he's thrown away his cigarettes.

JW: You have a good memory, I thought that if I could rob those arrogant liars of just one customer per month, it would be worth the effort.

CM: You had your work cut out for you, since they'd been placing print ads in many magazines and papers telling how doctors knew cigarettes were good for you.

JW: Doctors? How about Ronald Reagan? He used to do ads for Camels.

Frank Frazetta drew [the anti-smoking] ad, and to his everlasting credit, never took a dime for it. And he was a three-pack-a-day man until he was 50. And Archie Goodwin, who wrote the ad, also refused to take money for it. That's the kind of people I had working for me.

CM: I don't know their situations. Did they receive cancer from smoking?

JW: Years later I found out that each of them had people in their families who'd developed cancer. Whether it was lung cancer from smoking or not, I don't know. But I was proud to run the ad, even though we got flak for it.

CM: You got flak for the ad? From who?

JW: Who would you suspect?

CM: The guy who said, "Kid, we'll give you 50 grand for the back covers."

JW: That's a good guess, but it wasn't them. It was a family whose father worked in a tobacco related industry, making the cigarette paper. He thought I was taking food off his table. The demographic for all our magazines was teen age, so I felt the no-smoking ad was worthwhile. My first title had been called After Hours, which was a replica of Playboy. We certainly wouldn't nave run it there.

CM: You met Hugh Hefner several times, didn’t you?

JW: Yes. I don't know if you'll believe this, but his first publication was a ‘zine all about horror and monsters. Most of the world doesn't know that. It's like we're star-crossed, each publishing the other fellow's concepts. Hugh loves horror movies. I almost bought the franchise to open a Playboy Club in Philadelphia. At the time it wouldn't have worked out because in that city, in the early 1960s, you couldn't serve liquor on Sundays or after midnight on Saturday. We'd have lost a great deal of business. The laws are changed now. I really wanted to be a part of the emerging new world I saw springing up around me.

CM: It would have been quite a team to have you and Hef working together.

CM: It would have been quite a team to have you and Hef working together.

JW: Hugh Hefner is a genius in his own right and' never required an assistant. He needed to be the boss, just like Orson Welles, or Thomas Edison, the Wright Brothers, or any other "top dogs.

CM: There's another character I’d like to ask you about. Ray Ferry was all over the newspapers when he and Ackerman were in court. Do you have any thoughts on him?

JW: I don't think about him very often. He really means nothing.

CM: Here's another important question. The things that are in these movies and comics, such as ghosts, UFOs, Bigfoot, and so on. Does Jim Warren believe in any of this?

JW: No.

CM: Not to any degree?

JW: I like empirical proof. So I should say that a third of my mind is open to the reality of these things. The older I get the more open I am to the endless possibilities in the universe. If you want another opinion, check out Jimmy Carter. He claims to have seen a UFO. I talked with him about this exact same thing and he told me there was evidence that we've been observed since we began our first atomic bomb testing. This is not some crackpot, obviously. I believe he mentions something about it in his autobiography.

CM: As a final sentiment, how did you enjoy today's reunion with Forrest J Ackerman?

JW: Forry is still one of the beautiful people. I was fortunate to be working with him right from the start, since he is one of the most perfect wordsmiths of this generation. Perhaps of this century. Forry and I both have something in common in that we never entirely grew up. There is a bit of the child in both of us: I'd seen the grownup world and didn't like what it represented. It was a lot of takers, like those magazine distributors and cigarette makers we were talking about a minute ago. So I've been lucky to work in an area that appeals to the sense of imagination in all of us.

CM: You’re here on business for several weeks. Is there any chance that you're getting back into the monster publishing game after this long hiatus?

JW: All things are possible.

|

CM: It would have been quite a team to have you and Hef working together.

CM: It would have been quite a team to have you and Hef working together.

CM: Do you recall the print run of that first issue?

CM: Do you recall the print run of that first issue?